Rita is particularly horrified

by their discovery of the body in the dream narrative, Betty

helps her disguise herself. The two women then share a bed and

make love. Although deeply romantic, the scene is self-consciously

cinematic. With references to the hallucinatory obsessive love

story in Hitchcock’s Vertigo’s (1958), Rita’s hair is

cut and covered by a peroxide blonde wig although removed before

she gets into Betty’s bed. Betty comforts Rita : “You

look like someone else”. Physical masks and transformations

also of course allude to the artificiality, plasticity and phantasmic

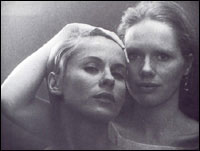

character of the actress. The double profile shot of the women

is also a knowing nod to Bergman’s Persona (1967) with

its erotic and weirdly symmetrical sisterly twinning. The love

scene moreover parodies female same-sex action in soft heterosexual

male pornography. Lynch’s erotic portrait thus incorporates

high and low cultural references. The particular focus on breasts

expresses both a surreal and Hollywood fixation. Lesbianism

even becomes a sexy joke as the young blonde Betty asks the

brunette amnesiac Rita “Have you ever done this before ?”

She responds “I don’t know...have you ?” However,

the first time the women make love they engage in warm, romantic

sex. Betty tells her : “I’m in love with you... I’m

in love with you.” It also, however, represents a dream

of erotic power which reproduces a masculinist Hollywood fantasy.

In the dream narrative, Rita becomes the yielding, responsive

lover of Betty. Her voluptuous, maternal body easily yields

to a fascinated, enamoured Betty. Betty is therefore herself

phallicised by Hollywood’s sexual fantasies and ideology.

|

|

|

|

All will not be well for Betty, however.

Rita is, as the mad seer Louise Bonner noted in mythic and

film noirish speak, “trouble”. As they sleep together, following

their love-making, Rita murmurs Silencio several times

and awakens her lover. She persuades Betty to accompany her

to Silencio which we find is an after-hours club. At the club,

a strange music hall, a sinister impresario tells the audience

in Spanish, French and English that the music is all a recording.

He orchestrates instrumental sounds by illustration. He creates

thunder. He stares at and appears to hypnotise Betty who convulses.

The music hall is bathed in blue light. Finally smiling with

a Svengali malevolence, he suddenly disappears in a puff of

blue smoke. We see a bizarre, cadaverous woman with a vortex

of blue hair also watching the spectacle. Another man then

introduces Rebekah del Rio who is in real life a Los Angeles

based singer. The women then witness an extraordinary rendition

of Roy Orbison’s 1961 hit Crying in Spanish and a-cappella

ILorando. Crying is an archetypal Orbison ballad,

lush and tragic. The narrative origins of Crying resonate

with the love story of Mulholland Drive which is effectively

a tale of unrequited love. Orbison confessed that the song

was inspired by a real life love affair, specifically his

response to the sight of an old love lost-crying. Crying,

it seems, is a song which inspires extreme emotion. About

Crying, the singer Tori Amos has amusingly alleged :

“If I’m honest this track keeps me out of jail. I put the

steak knife down and pick up a hanky.” Thus it is a ballad

to pacify the homicidal woman ! The Silencio sequence

is indeed in Mulholland a powerful, romantic time space

which stops us in our tracks. This is largely provided by

Crying. It does nothing less than crystallise love.

Crying, moreover, is the stuff of dreams. As Tom Waits has

precisely eulogised : “Roy Orbison’s songs were not

so much about dreams as like dreams.” Mulholland’s

Crying is not only true to the tale of tragic love,

emotional intensity and the oneiric power of the original

but does more. Beautifully executed in pure and solitary a

capella, Crying’s dream is intensified in Ilorando

as it is adapted to a young woman’s singular and absolute

yearning for another. It is surreally visualised as the theme

of a magical place and dream. ILorando is not only

innocent and natural but associated with a singular eroticism.

The extremely emotional power of Crying and its role

as the theme of an occult place allows it to be linked portentously

to evil and death. Moreover, it is given more universal power

in translation as it bound to other tragic myths. With a painted

crimson tear under her eye, Rebekah del Rio sings as the mythic

figure Ilorana. She imitates a Mexican wailing woman

grieving in advance of tragedy. For the women, the song represents

the apex of their love although the tale is ultimately unrequited.

The response to Ilorando is crying.

|